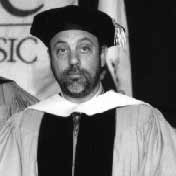

Commencement 1993

Billy Joel Delivers Commencement Address

Thank you President Berk, trustees, faculty, staff and students of Berklee, and guests. Johnny Mandel, who is also being honored here today.

I understand that there are over five hundred students in this graduating class. What an amazing thing. When I was a young musician, the only option available to pursue secondary education in music was to attend a classical conservatory. Obviously, I didn't choose that route, and although the one I ended up taking has been rather circuitous, I am truly pleased that the road has twisted and turned its way up the East Coast to Boston. The Berklee College of Music represents the finest contemporary music school there is, and I am honored to be here with you this morning to celebrate the 1993 Commencement.

I have been asked many times, "Why do musicians give so much time to charitable causes?" I know a few musicians who are motivated by pure guilt—the result of a dissolute and misspent youth combined with the onset of remorse and middle age. I am not as remote from these few as I would like to think. Some are motivated to activism by a sincere idealism, which musicians and artists in general must have in spades to be able to deal with the disappointments and cynicism we all encounter in what seems an often endlessly futile labor of love. Perhaps it is mainly because musicians want to be the loud voice for so many quiet hearts.

Maybe it's because we know what it is like to be completely alone, to be unemployed, to have to struggle. Historically, musicians know what it is like to be outside the norm—walking the high wire without a safety net. Our experience is not so different from those who march to the beat of different drummers. We experience similar difficulties, weakness, failures and sadness, but we also celebrate the joys and successes—these are the things that we translate and express in music.

Maybe it's because we know what it is like to be completely alone, to be unemployed, to have to struggle. Historically, musicians know what it is like to be outside the norm—walking the high wire without a safety net. Our experience is not so different from those who march to the beat of different drummers. We experience similar difficulties, weakness, failures and sadness, but we also celebrate the joys and successes—these are the things that we translate and express in music.

And still, we hear the same question: So when are you going to get a real job? How many times have you been asked this question or some incarnation thereof? Beethoven heard it. John Lennon heard it. Milli Vanilli heard it. Bob Marley heard it. Janis Joplin heard it. Tchaikovsky heard it. Charlie Parker heard it, Verdi, Debussy. When I was 19, I made my first good week's pay as a club musician. It was enough money for me to quit my job at the factory and still pay the rent and buy some food. I freaked. I ran home and tore off my clothes and jumped around my tiny little apartment shouting "I'm a musician, I'm a musician!" It was one of the greatest days of my fife, just to be able to make a living as a musician alone, to earn money doing what I loved to do.

Artist—musicians, painters, writers, poets—always seem to have had the most accurate perception of what is really going on around them, not the official version or the popular perception of contemporary life. When I look at great works of art or listen to inspired music, I sense intimate portraits of the specific times in which they were created. And they have lasted because someone, somewhere felt compelled to create it, and someone else understood what they were trying to do. Why do we still respond when we bear the opening notes of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony—DA DA DA DA? Or Gershwin's Rhapsody In Blue? Or Little Richard's Tutti Fruitti? Because when we hear it we realize that we are still bound by a common emotion to those who came before us. Like family, we are irrevocably tied to each other because that same emotion still exists today. This is what all good musicians understand.

I can't think of one person I've ever met who didn't like some type of music. More than art, more than literature, music is universally accessible. For whatever reason, not all people are born with the particular gift that we have: the gift of being able to express ourselves through music. And, believe me, it is a gift. But people who don't have this ability still need to find a way to give a voice to what they're thinking and feeling, to find something that connects them with others. As human beings, we need to know that we are not alone, that we are not crazy or that we are all completely out of our minds, that there are other people out there who feel as we do, who live as we do, who love as we do, who are like us.

Music does this in such a complete and uncomplicated way. There is great magic in this. In a way, we are magicians. We are alchemists, sorcerers and wizards. We are a very strange bunch. But there is great fun in being a wizard. And great power, too.

Nowadays, we are living in a time when American popular music is finally being recognized as one of our most successful exports. The demand is huge. The whole world loves American movies, blue jeans, jazz and rock and roll. And it is probably a better way to get to know our country than by what the politicians or airline commercials represent. Musicians now find themselves in the unlikely position of being legitimate. At least the IRS thinks so. Once they discovered that we were actually capable of making "money," the free ride was over. No one eludes Uncle Sam's tax man anymore like they did in the old days when we were outlaws, hippies, beatniks and weirdoes and—the most shadowy group of all—jazz players! No, we're all corporations and contractors and production companies now—and by the way, I hope most of you have taken some basic accounting courses and have a lawyer in the family. You're going to need both.

So why do musicians give so much time to charitable causes? There are many reasons, but the most humanitarian cause that we can give our time to is the creation and performance of music itself. That is the gift we have been given, that is our destiny and our usefulness as human beings in the short time we have in this world. And that's plenty of reason.

And I hope you don't make music for some vast, unseen audience or market or ratings share or even for something as tangible as money. For though it's crucial to make a living, that shouldn't be your inspiration or your aspiration. Do it for yourself, your highest self, for your own pride, joy, ego, gratification, expression, love, fulfillment, happiness—whatever you want to call it. Do it because it's what you have to do. And if you make this music for the human needs you have within yourself, then you do it for all humans who need the same things. Ultimately, you enrich humanity with the profound expression of these feelings.

Now I have been both praised and criticized in my time. The criticism stung, but the praise sometimes bothered me even more. To have received such praise and honors like this has always been puzzling to me when I consider myself to be an inept pianist, a bad singer, and a merely competent songwriter. What I do, in my opinion, is by no means extraordinary. I am, as I've said, merely competent. But in an age of incompetence, that makes me extraordinary. Maybe that's why I've been able to last in this crazy business. I actually know how to play my ax, and write a song. That's my job.

So when are you going to get a real job? When are you going to get serious about life? I have news for them: When are you going to get a real job? This is a real job—as real as a doctor, a teacher, or a scientist and just as important as and very similar to healing, teaching and inventing. But even more fun because we have that wizard and sorcerer bit going for us. I have said before to those who have expressed doubts and misgivings about their ability to live this kind of life maybe they shouldn't try, because being a musician is not something you chose to be, it is something you are, like tall or short or straight or gay. There is no choice, either you is or you ain't.

Now, I'm sure it must be daunting to come in times of financial distress and unemployment. But consider this: have you Iistened to the radio lately? Have you heard the canned, frozen and processed product being dished up to the world as American popular music today? What an incredible opportunity for a new movement of American composers and musicians to shape what we will be listening to in the years to came. While most people are satisfied with the junk food being sold as music, you have the chance and the responsibility to show us what a real banquet music can be. You have learned the fine art of our native cuisine—blues, jazz gospel, Broadway, rock and roll and pop. After all this schooling, you should know how to cook! So cook away and give us the good stuff for a change. Please. We need it We need it very, very much. Congratulations and good luck!